1976 – Rainbow Rising

It’s 1976 and Richie Blackmore has, ever-so-slightly, loosened his grip on his band and dropping the “Ritchie Blackmore’s…” prefix, it is now simple called Rainbow. Arguably he released his grip entirely on the bassist, drummer and keyboard player, having fired all except Ronnie James Dio, and recruiting Cozy Powell, Tony Carey and Jimmy Bain to fill their places.

It’s 1976 and Richie Blackmore has, ever-so-slightly, loosened his grip on his band and dropping the “Ritchie Blackmore’s…” prefix, it is now simple called Rainbow. Arguably he released his grip entirely on the bassist, drummer and keyboard player, having fired all except Ronnie James Dio, and recruiting Cozy Powell, Tony Carey and Jimmy Bain to fill their places.

Further evidence of Blackmore’s willingness to share the spotlight with the rest of the band is found as the album opens with over a minute of keyboard solo introducing Tarot Woman. People talking of the great keyboard intros of rock of cite Genesis’s Watcher Of The Sky or even Ozzy Osbourne’s Mr. Crowley, but surely Tony Carey’s work here wins hands down? Then, at 1m30, in come the band with a one of Blackmore’s finest driving riffs and Cozy Powell and Jimmy Bain thundering along behind, and Dio… well, I don’t think it’s too hyperbolic to say that the moment he opens his mouth you can tell he’s going to change the world of rock vocals.

Run With The Wolf is a more swaggering riff, and here the guitar work is more apparent, but with the same monstrous rhythm section work (Cozy in particular is in fine fettle on this) and more of that wonderful, mix of grit and wail that characterises Dio’s voice. Starstruck and Do You Close Your Eyes follow and though for me they’re the weakest tracks on the album, I only say that because they’re up against impossible competition. They’re great, straight out rock tracks (with Do You Close Your Eyes in particular having some very tasty hammond work in there) and if the whole album were full of songs like that it would still be a good solid album. But it isn’t, because side B is approaching, and side B contains just two songs.

Starstruck. Opening with one of Cozy’s trademark four-limbed drum workouts and ending with a repeated orchestral pattern which at 2 minutes ought to be too long but for Dio’s inspired extended vocal ad-libbing, this has to be one of the finest moments of rock history. Play it loud, in the dark with your eyes closed.

I will have to go on record as saying that though I know it alienates many people, I really have no problem at all with the wizards and demons imagery that, starting here, came to characterise a lot of Dio’s lyrical output. Something as majestic as this needs something otherworldly to match the music. Singing bawdy, macho lyrics about women and cars, or complaining about The Man and how dull work is just wouldn’t do here.

As the song finally fades you wonder how you could possibly follow something like that, and a quick and obliging drum fill from Cozy brings in A Light In The Black, and its pounding but straightforward riff seems like the perfect, stripped-back answer. But the band trick you and in fact though it seems pretty straight, before you know it they’ve launched into two monumental solos, starting with Tony Carey on crunchy, distorted synth and then Blackmore doing his thing at the peak of his abilities. You can hear that this track was written to be played live and to take over as a vehicle for the sort of pyrotechnics that used to accompany Space Trucking on Deep Purple tours. But this isn’t just technical show boating, with virtuosity on both sides being interspersed with crafted melodic lines and doubling each other’s lines.Fading out at the end of this album would feel like a cop-out and thankfully once the vocals return they make their way towards a colossal and almost stage-like ending.

Though the album’s short at just over half an hour, I usually find myself sitting in silence for a few minutes after it has finished, and I’m happy to tack them on to its notional length.

Sadly, though this line-up would go out on tour, Ritchie’s infamous antics and apparently impossible to work with personality meant that Jimmy Bain was out before the next album was started. Tony Carey, whose contributions on Rising are something special, didn’t last for the full recording of Long Live Rock ‘n’ Roll, and before Down To Earth was started he lost Dio. One more album after that and Cozy Powell had walked too.

But here on Rising the band are (to use a cliché) firing on all cylinders and like with so many of the albums that I find make my favourites list, it’s this magic band chemistry that lifts it from being simply a good album to one where there seem to be no lulls while you’re waiting for the next “good bit” to come along.

1975 – Jeff Beck, Blow by Blow

A bit of a change of direction for this one, and an album I found quite late compared with others I’ve listed so far. Jeff Beck used to be a name I associated with Hi Ho Silver Lining and nonsense quotes from guitarists about having “notes on his guitar that no-one else has.”

A bit of a change of direction for this one, and an album I found quite late compared with others I’ve listed so far. Jeff Beck used to be a name I associated with Hi Ho Silver Lining and nonsense quotes from guitarists about having “notes on his guitar that no-one else has.”

It was Where Were You? from Guitar Shop that I heard first and suddenly I could understand what people were going on about. The rest of the album though left me somewhat cold and a friend suggested I pick up Blow By Blow and Wired instead.

As an instrumental album full of segues and changes within pieces I’m actually not entirely familiar with most of the pieces by name, but right from the get go on You Know What I Mean it’s clear that what we’re listening to is not Jeff Beck per se, but the Jeff Beck Band. And it’s a really tight, funky band, crammed with talent. Max Middleton on keyboards stands out for me, though I learned later than Stevie Wonder helped out here and there too.

Having said I don’t know the track names, the exception is Scatterbrain which a six minute slice of perfection with some superb drumming, great lead work from Beck and Middleton, and orchestral backing which just about stays on the right side of being interesting without taking over, and a driving, tension-building main theme which kicks in whenever things are starting to get a little too safe.

Scatterbrain is followed by Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers, which is one of those tracks that showcases what people mean when they talk about notes on Jeff Beck’s guitars that don’t exist for anyone else. His phrasing, dynamics and control of notes on a piece like this is simply astounding.

After a few more changes of mood the album finishes with Diamond Dust, which again brings in an orchestral backing. This time its use is more prominent and the string section features more on a par with the rest of the musicians, being given its own share of the limelight before dreamily closing out the album.

In a way I find it hard to explain what it is I like about this album when placed along side other things on my list, but clearly from my playing habits it’s right up there for me. It’s an album I put on over and over, particularly when I’m in the mood for something that will occupy my brain without distracting me too much. For all the occasional blitzes of excitement, I find it a very soothing album to have on without it simply being background music. A rarity.

1974 – Queen II

After a promising debut album, recorded in down time between bigger artists’ use of the studio, Queen had the confidence to demand more time on their own terms. The result, the somewhat unimaginatively title Queen II is their first masterpiece.

Divided into sides White and Black rather than A and B, with pieces seguing into each other and (with the exception of Roger Taylor’s Loser In The End) a strong lyrical thread of fantasy there was more than a hint of “concept” to this album.

Divided into sides White and Black rather than A and B, with pieces seguing into each other and (with the exception of Roger Taylor’s Loser In The End) a strong lyrical thread of fantasy there was more than a hint of “concept” to this album.

Opening Side White is a Procession, starting with a bass drum heart beat (in 3/4) and Brian May’s soon to become very familiar layered, violin guitar sounds leading into the first proper track, Father To Son. Although there is an underlying verse/chorus structure at the start it feels much more free, and this only continues as the song plays out through new theme after new theme, never quite stopping for long enough to let the listener settle and by the time it eventually comes circle only four minutes have passed. This is a song that could have easily been stretched to double its length but that is perhaps part of its appeal. In addition, the guitar work really gives an early view of Brian’s versatile but easily recognised style and the harmonies are recognisably the Queen that would eventually be producing Bohemian Rhapsody and the like.

The end of the track segues smoothly into the much gentler, sadder White Queen. Again, the song structure leaves the listener guessing for a lot of the song and while there is a more noticeable verse pattern they are anything but straightforward and predictable and there’s not really a chorus as such, more of an ever-changing set of alternatives to the verse. The track builds to a climax through an acoustic guitar solo which sounds almost like a sitar, and then eases out.

The first of the slightly out-of-concept tracks is the Brian May vocal track, Some Day, One Day which is one of my favourite things he’s done acoustically. Layered guitar lead lines weave over a very jangley acoustic guitar and vocals line with John Deacon’s bass work being well worth a little bit of attention in its own right.

Next up is Roger Taylor’s The Loser In The End which is even more out of character but forgivably so with its quirky drum intro and mini-solo and again both Brian and John play out of their skins with some outstanding parts. And of course, in any normal rock band, Roger Taylor would have been the lead vocalist. But normal rock bands don’t have Freddie Mercury.

Speaking of Freddie, his absence for the last two songs is rectified at the start of Side Black with the entry of the quite literally awesome Ogre Battle. Swirling cymbals, trademark “Ahh!” vocals and a guitar part which Brian May learned and played backwards, then reversed to give an otherworldly feel to the intro and then at one minute, Freddie starts telling his story. The relentless riffing and interjected vocal harmonies and screams make this a glorious track for turning up really loud.

Next up is The Fairy Feller’s Master-stroke, inspired by a Richard Dadd painting. More frenetic guitar and vocal lines are joined by a harpischord (used to surprisingly good effect) and by the time you reach Nevermore you’re ready for the light relief it provides.

The March of the Black Queen begins with ominous piano and guitar trills before leading through another disorienting array of themes and sections, building into a chaotic and poly-rhythmic chaos before settling for a a few verses of piano and vocal with interjections from the drums and guitar. The tempo picks up again and the song heads towards its false ending before a surprise epilogue bridges into the wall-of-sound track Funny How Love Is.

And then we’re at the last track, which is the same track which closed their first album. Except this time they’ve finished writing it. With added lyrics, a raised tempo and some more structure Seven Seas Of Rhye is transformed from its original somewhat flat version into something that would give Queen their first proper taste of chart success.

I suppose as an album it’s less polished than A Night At The Opera, but some of that rawness and the explosion of creativity you can feel from a band who finally have space to explore and to let their combined and individual genius shine results in something that I find lifts the album. It’s tied with ANATO and Innuendo as my favourite of Queen’s albums, and if you put a gun to my head, I might have to pick it above the other two.

This year’s Honourable Mention goes to Lucifer’s Friend for Banquet. This is a really, really tough call because Banquet is a also phenomenal album. John Lawton is one of my favourite singers and the rest of the band are superb and I have no idea why they aren’t more famous. Progressive rock with jazzy, latin leanings and various orchestral instruments (including a really wild clarinet solo), this one only lost out to Queen II because the latter was such a formative album for me. I think in truth, I listen to Banquet more, but I’m going to stay with my original pick.

This year’s Honourable Mention goes to Lucifer’s Friend for Banquet. This is a really, really tough call because Banquet is a also phenomenal album. John Lawton is one of my favourite singers and the rest of the band are superb and I have no idea why they aren’t more famous. Progressive rock with jazzy, latin leanings and various orchestral instruments (including a really wild clarinet solo), this one only lost out to Queen II because the latter was such a formative album for me. I think in truth, I listen to Banquet more, but I’m going to stay with my original pick.

1973 – Selling England By The Pound

“Can you tell me where my country lies?”

I had listened to several later Genesis albums before delving into their past, and though I knew that this was going to be different, I wasn’t expecting to be met by a slightly wobbly, solo vocal line to open the album. It’s as brave an opening as I’ve ever heard, and once I’d got over the surprise at it I fell in love with it.

I had listened to several later Genesis albums before delving into their past, and though I knew that this was going to be different, I wasn’t expecting to be met by a slightly wobbly, solo vocal line to open the album. It’s as brave an opening as I’ve ever heard, and once I’d got over the surprise at it I fell in love with it.

The album unfolds gently, step by step from this unassuming starting point. Not with a sense of anticipation and drama, but with a gentle sense of wading in until you suddenly realise you’re in the up to your neck in midst of the first, frantic instrumental section two and a half minutes in. Dancing With The Moonlit Night continues on its course, changing mood and feel and then, almost as surprising as its beginning, it finishes with a serene two minute fade out over pluckings, mellotron strings, flute and all other manner of other textures.

Like a lot of early Genesis it is full beautifully melodic shadings and interplay between the lines played by Banks, Gabriel, Hacket and Rutherford, and some fabulously creative, intricate and just plain musical drumming from Phil Collins. None of the many changes in feel or rhythm seem to be abrupt or out of place.

I Know What I Like is a single, but it’s quirky, well played and fun. There’s some really lovely bass playing in throughout and the blend of Gabriel and Collins’ voices works well. There’s lots of little percussion and flute moments going on in the background with nothing really stepping out and brashly demanding the full spotlight, something which could be said for much of the album.

Firth of Fifth is something of a tour-de-force for Tony Banks, starting with a piano solo. The transition into the first verse is an unexpected change of direction, but it makes sense later when the piano intro is reprised later on in the middle instrumental on synthesizer. Before we get to that though there’s one of my favourite Peter Gabriel flute moments, and a beautifully piano build-up. Phil’s drumming is again beautifully complementary to the lead instruments at each stage and to the piece in whole, and then there’s a sublime guitar lead part (it’s not really right to call it a solo in the traditional sense). After a while we realise we’ve come full circle and the vocals make a brief reappearance before another delicately arrange fade-out.

More Fool Me. Well… this one gets a lot of negative reception. It’s a Phil Collins vocal piece. It’s not exactly bland, it’s not exactly without merit. It feels a little out of place on the album but I don’t hate it the way many people do, and I don’t skip it, but it is probably for me one of the few areas I think they could have found something better to do.

The Battle of Epping Forest is often cited as Peter Gabriel’s characters, lyrics and concepts getting out of control and spoiling an otherwise good track. It’s certainly quite a lot being shoe-horned in but I think the writing of the whole piece, not just Gabriel’s parts, is a more challenging to the listener. When I’m in the for listening closely, it has got some absolutely wonderful lines and interplay and some of the finest drumming I’ve heard from Phil Collins outside of Brand X, but it is unquestionably a more angular, fractured and attention-grabbing piece. My least favourite part is the middle “The Reverend” section though even that is something I wouldn’t say I dislike and at times I enjoy it as much as anything. I suppose the bottom line on this song is that I have to be in the mood for, unlike Moonlit Night, Firth of Fifth and Cinema Show which I could listen to any time.

And then there’s After The Ordeal, which provides the sort of musical interlude I strive to put on albums I write to break up the larger, more unwieldy pieces but without ever feeling like a piece of filler which has no merit of its own.

The Cinema Show is another absolutely stunning piece of composition and band interplay. Whatever may have happened to the relationship between the band members over time, here they were all having their moments to shine, never at the expense of each other, and often in combination. The piece goes through several vocal sections and different themese before reading, for me, one of the high points of Genesis’s output at about 6 minutes. A classic building section in 7/8 with tasteful synth lead work and then a glorious mellotron choir. And just when you think it will find its way back the verse vocals, you found you’ve been taken down a different road to Aisle of Plenty. More of a musical epilogue than a piece in its own right, it reprises the theme from Dancing With The Moonlight Knight, with some clever lyrical content from Peter Gabriel (actually, the whole album is riddled with word play and clever metaphores and imagery). In any case, it is a perfect ending to a really superb album.

Tags: album-of-the-year1972 – Close To The Edge

The year is 1972, and Yes are being catapulted to new heights by the success of their late 1971 release, Fragile. Does the curse of pressure to produce a follow-up album strike them down? Uh… no.

Close To The Edge is a masterpiece from start to finish. The title track is a sprawling gem of a composition, starting with bird song and wind and three minutes of instrumental chaos interrupted by block vocals (not a million miles away from the ideas which opened Salisbury, though stylistically and technically it is on a different level). It then breaks into an almost shockingly melodic theme, but the relief doesn’t last long as it starts to get harmonically complex again before the first verse pattern kicks in. All five musicians seem to play different rhythms, with the drums and bass heading in one direction, the vocals in another, and the guitar and keys managing to find even more variations on things to do in between. Rhythmically and generally in terms of complex interplay that manages to hang together, it’s a work of genius.

Close To The Edge is a masterpiece from start to finish. The title track is a sprawling gem of a composition, starting with bird song and wind and three minutes of instrumental chaos interrupted by block vocals (not a million miles away from the ideas which opened Salisbury, though stylistically and technically it is on a different level). It then breaks into an almost shockingly melodic theme, but the relief doesn’t last long as it starts to get harmonically complex again before the first verse pattern kicks in. All five musicians seem to play different rhythms, with the drums and bass heading in one direction, the vocals in another, and the guitar and keys managing to find even more variations on things to do in between. Rhythmically and generally in terms of complex interplay that manages to hang together, it’s a work of genius.

There’s a spacious musical soundscape in the middle with gentle vocals by Anderson and (I’m guessing) Squire and Howe. Again, nothing’s quite straightforward here and rather than harmonising with Anderson, the two second voices sing a second, counter-melodic line which weaves in and out of the main line. A masterful change of rhythm and time signature is introduced between contrasting sections of vocals and cathedral organ before Wakeman elbows his way to the fore with one of his jarring twanging, almost out of tune Moog sounds (but in a good way) and then plays one of those Hammond solos that I seem to forget he’s capable of playing, and then the track comes full circle back through the first verse pattern to the bird song and wind that opened the track.

Throughout the piece (and indeed his career) Jon Anderson’s lyrics are characteristically opaque, but the way he uses them on Close To The Edge shows them more as sounds than actual words, an effect made all the more apparent by the way he ties phrases to specific musical phrases or leitmotifs.

And You And I relaxes the pace and style, with a strongly acoustic feel (somewhat interrupted by the sound of someone playing through something like a Leslie speaker). The piece morphs through a couple of different parts including a somewhat symphonic section but the main impression I’m left with is of the piece is as a ten minute chill out between the two pieces bookending the album. Again, this is no bad thing but it is a track that I feel benefits from its position on the album and which I probably wouldn’t listen to on its own.

The third and final track on the album, Siberian Khatru, is led by Steve Howe’s blistering guitar riff augmented by Wakeman’s odd melltron chords. The rhythm is once again all over the place and there is so much to listen to with no parting being resigned to simple accompaniment of the others.

The album is full of intricate arrangements all the way through and so really rewards repeated listening. The playing is always very tight and there is strong confidence evident in everyone’s playing at all times which is probably necessary in making pieces like this work without sounding like a mess.

I should make special mention of Squire’s playing which really does show why he is so highly rated as a bassist. While he and Bruford certainly manage the usual rhythm section duty of holding things together, Squire also plays his lines very much on an equal level with the keyboard and guitar in the sense of playing an important part in the melodic and harmonic structure of the pieces. In fact, if you put a gun to my head and asked me to pick out a single star of the album, I think it would be Squire.

The album clocks in at what might be seen as a measly 38 minutes, but the amount of ground that they cover in that time makes it feel like a complete album. Playing a little game of “pick the track you’d add to this album,” I don’t think I’d change anything: It’s a five star album as it stands.

Tags: album-of-the-year1971 – Uriah Heep, Salisbury

1971 was amongst the hardest years for me to choose an album from. In the end Deep Purple’s Fireball missed out because In Rock was the winner for 1970. I chose Uriah Heep’s Salisbury over both ELP’s Tarkus because, though they are both albums made special by their title track, I find Salisbury to be an album of songs with a shining gem of a piece, where Tarkus is a shining gem of a piece surrounded by filler. So, Salisbury it is then.

The album opens in dramatic style with Bird of Prey (unless you live in the US, which has a different track listing!) interspersing guitar riffing with stacked vocal “ahhs”. Byron’s mid-high range can be a little thin at times but generally his voice is good and the effect here is unusual and grabs attention. True to style, though it starts like a fairly straightforward rocker, the track has a few changes of pace and extended ideas which make it more interesting.

The album opens in dramatic style with Bird of Prey (unless you live in the US, which has a different track listing!) interspersing guitar riffing with stacked vocal “ahhs”. Byron’s mid-high range can be a little thin at times but generally his voice is good and the effect here is unusual and grabs attention. True to style, though it starts like a fairly straightforward rocker, the track has a few changes of pace and extended ideas which make it more interesting.

The next four tracks wander back and forth between styles with The Park being a pleasant laid back drifter of a number, Lady In Black an driving acoustic number sung by Ken Hensley, and Time To Live and High Priestess being rockier.

But really, this album is all about the title track. A magnificent piece of progressive rock mixing a small orchestra with the rock group. Unlike Jon Lord’s Concerto which is quite classical, this is a more standard rock instrumentation using the orchestra more in “horn section” fashion. As a piece, it goes through several well-defined sections. Opening with orchestra and hammond, broken up by a woodwind break, it finally comes together rhythmically after about two minutes and before breaking into a vocal section.

Lyrically it’s pretty banal — the story of the birth and death of a love affair, going full circle into the arrival of the next love — but for some reason the lyrics don’t detract much for me. It’s well sung. Actually, those vocals deserve mention: having previously said that Byron’s voice can be a bit thin at time, he pulls a blinder in this track ranging from soft and delicate to powerful and resonant, with very little use of his scream register.

It’s a beautifully orchestrated piece, both in terms of the writing of the individual lines and in terms of the wider development from section to section. It contains some fabulous hammond and guitar work, and the orchestra feels very much and choral parts feel like an inherent part of the composition rather than something thrown on top of a rock band in a kind of just-add-bombast way.

All in all it’s a track which serves as a shining example of one approach to the dangerous classical-meets-rock territory which so often falls flat one way or another.

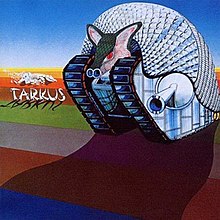

Honorable Mention: Tarkus

If the contest were between the title tracks of the album alone, I would be writing this article about Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s Tarkus. A monstrous tour de force, dominated by Keith Emerson’s hammond playing, but with plenty of other things going on to keep it interesting.

If the contest were between the title tracks of the album alone, I would be writing this article about Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s Tarkus. A monstrous tour de force, dominated by Keith Emerson’s hammond playing, but with plenty of other things going on to keep it interesting.

Perhaps it’s a little unkind to describe the other tracks on the album as filler, but while there is some nice work on there, they certainly pale in comparison to the title track, and as much as I like light-hearted tracks (Genesis’s Harold The Barrel would make my Desert Island Discs collection) I find both Jeremy Bender and Are You Ready Eddie? to be all light and no heart.

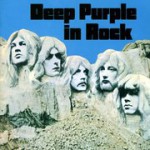

Tags: album-of-the-year1970 – Deep Purple In Rock

Funnily enough, seminal though it is, I did actually have to think hard whether there was anything else in 1970 that warranted inclusion in my list ahead of In Rock. I suppose the truth is that it’s such an obvious choice that I felt uncomfortable picking it as my first selection. In the end though, there really is no contest.

The album kicks off with a cacophony of guitar, primarily, and band thrashing their way around an opening chord before fading into Jon Lord’s odd chromatic keyboard intro to Speed King. Then we get an earful of Ian Gillan. It’s a hell of an opening statement for an album, and must have seemed even more so back then.

The album kicks off with a cacophony of guitar, primarily, and band thrashing their way around an opening chord before fading into Jon Lord’s odd chromatic keyboard intro to Speed King. Then we get an earful of Ian Gillan. It’s a hell of an opening statement for an album, and must have seemed even more so back then.

One of the immediate things that always strikes me when I return to this album having not listened to it for a while is that as heavy and aggressive as it is, the proficiency of the playing really shines through. This isn’t like a lot of crude heavy rock and metal where the aggression seems to come first — this album is heavy, but also tight, dry, and punchy, and manages to get enough light and shade in without losing that hard edged focus.

In order to try to go toe-to-toe with Ritchie Blackmore’s guitar sound, Jon Lord ditched his Leslie speaker for much of the album and played through a heavily distorted guitar amp, without a much reverb or anything else to smooth out the edges. That much distortion makes a keyboard a remarkably unforgiving instrument to play and yet it’s skilfully and intelligently played and it really contributes to the sense of tightness of the album.

So, stand out tracks? Well Child In Time is, far more so than Smoke On The Water for me, the quintessential Deep Purple track of the era. The extended solos in the middle, Gillan’s vocal work which set the benchmark for rock screamers (though in the live versions he sounded if anything a little rougher and less sterile). Aside from that, they’re all great tracks but I think Flight of the Rat is an overlooked gem — very catchy and with some fabulous keyboard work and some unexpected changes of direction whenever it starts to sound in danger of getting stuck in a rut. Also worth mention is Living Wreck, in particular has got some glorious rhythm work by everyone, with Paice’s drums really shining.

On In Rock, Deep Purple were firing on all cylinders and they sound like a band with a strong sense of identity and purpose, something that started to unravel as egos came more into play over time. While later albums touched highs in other ways, they never quite sustained the sense of intensity through an album the way they did here.

Tags: album-of-the-year